Online Viewing Room

Rebekka Steiger

boxing the compass

March 22 - September 20, 2020

Essay by Aoife Rosenmeyer, published in the exhibition catalogue Rebekka Steiger - boxing the compass, Kunsthaus Grenchen, 2020

HOW ARE WE IN A PLACE?

What planet pulls us close? Leonardo da Vinci called the dimming and blueing of landscape when seen in the far distance, and its mimicry in painting, aerial perspective.

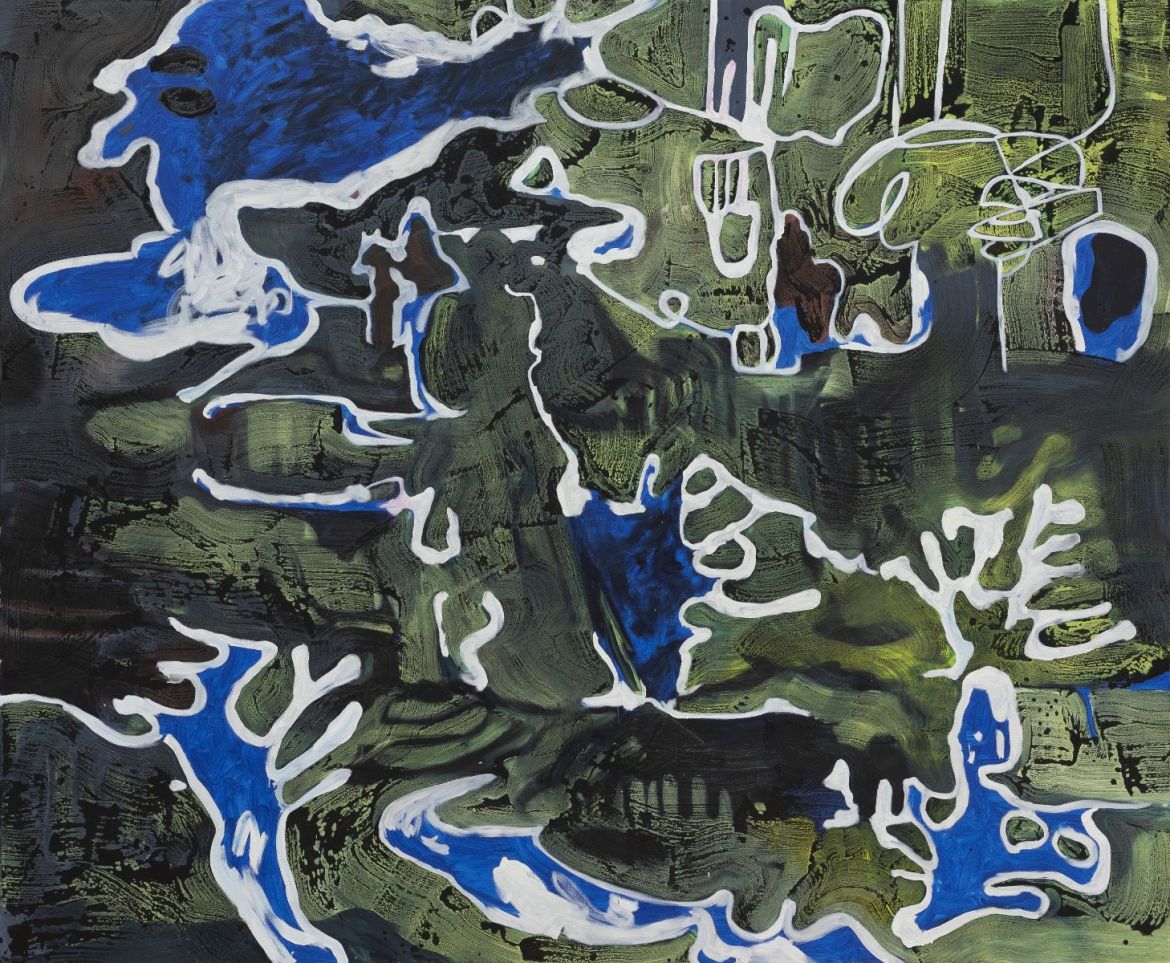

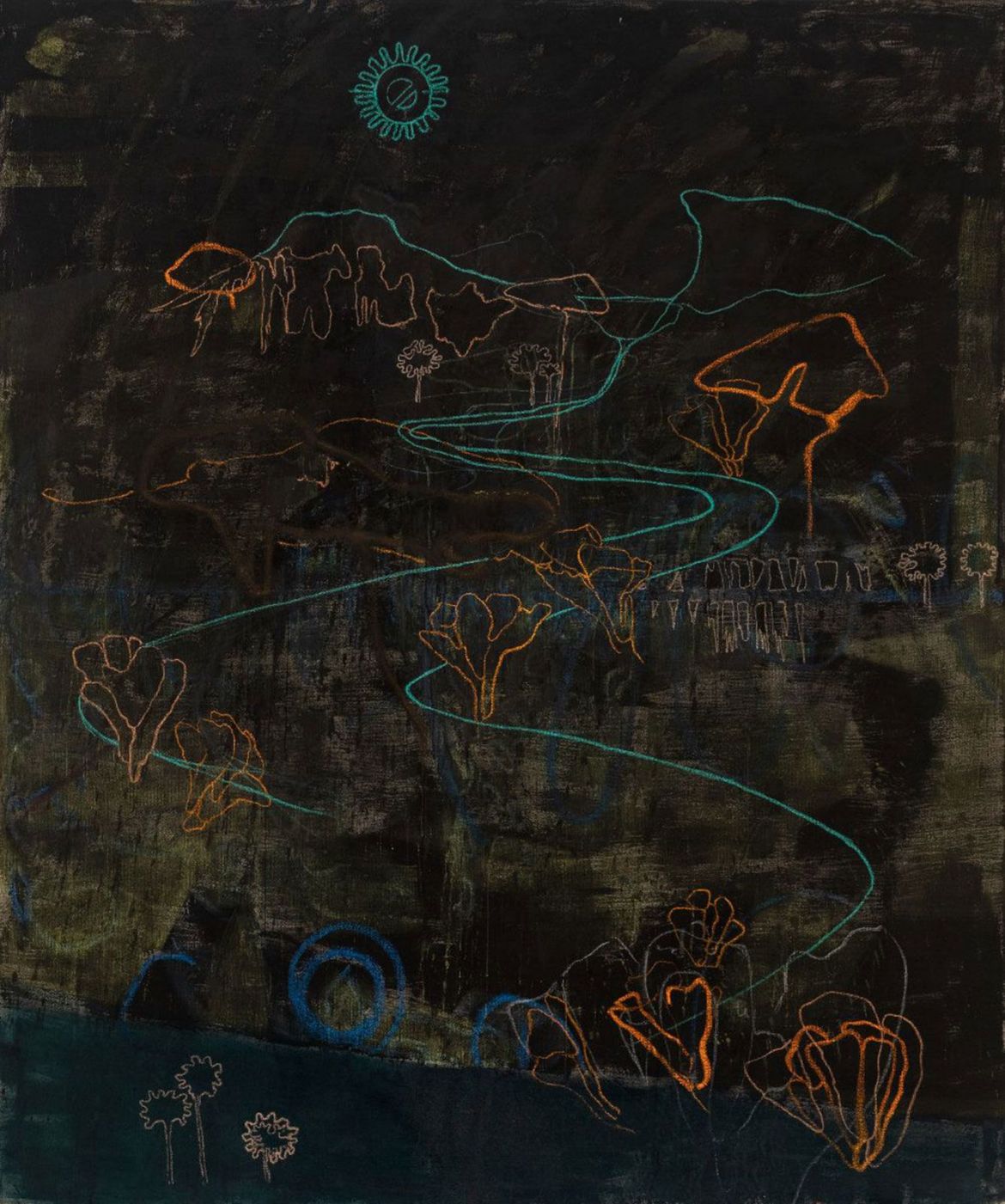

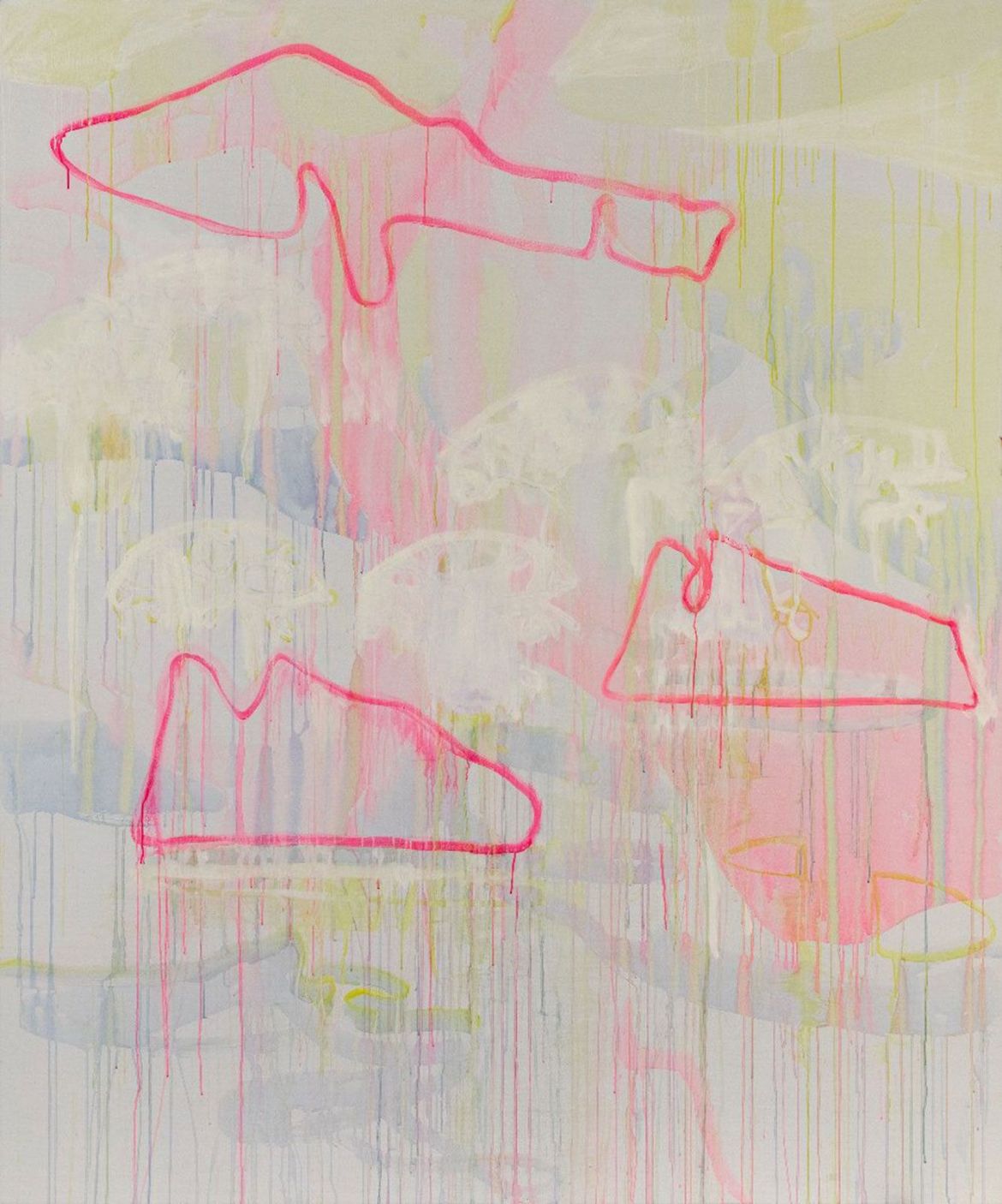

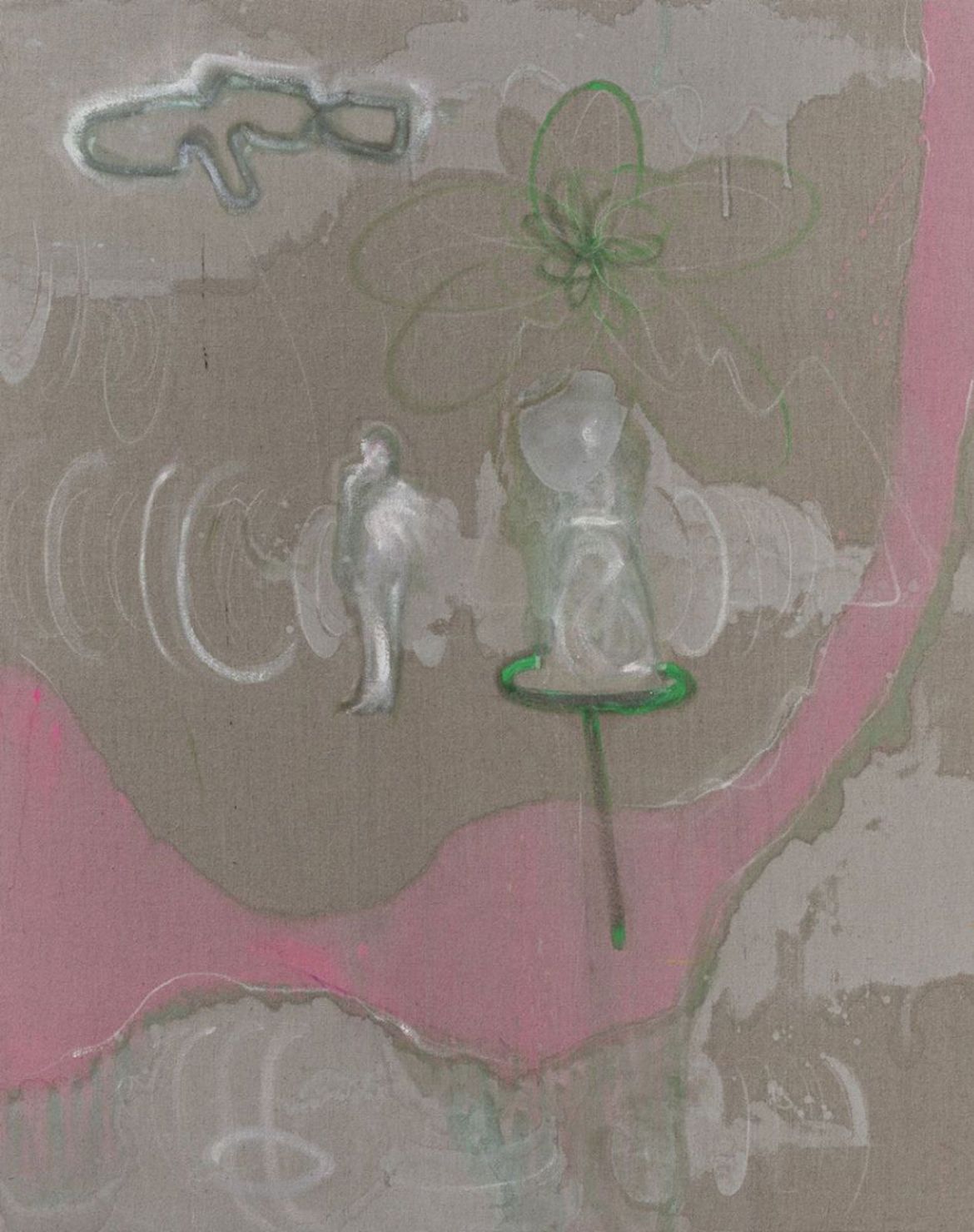

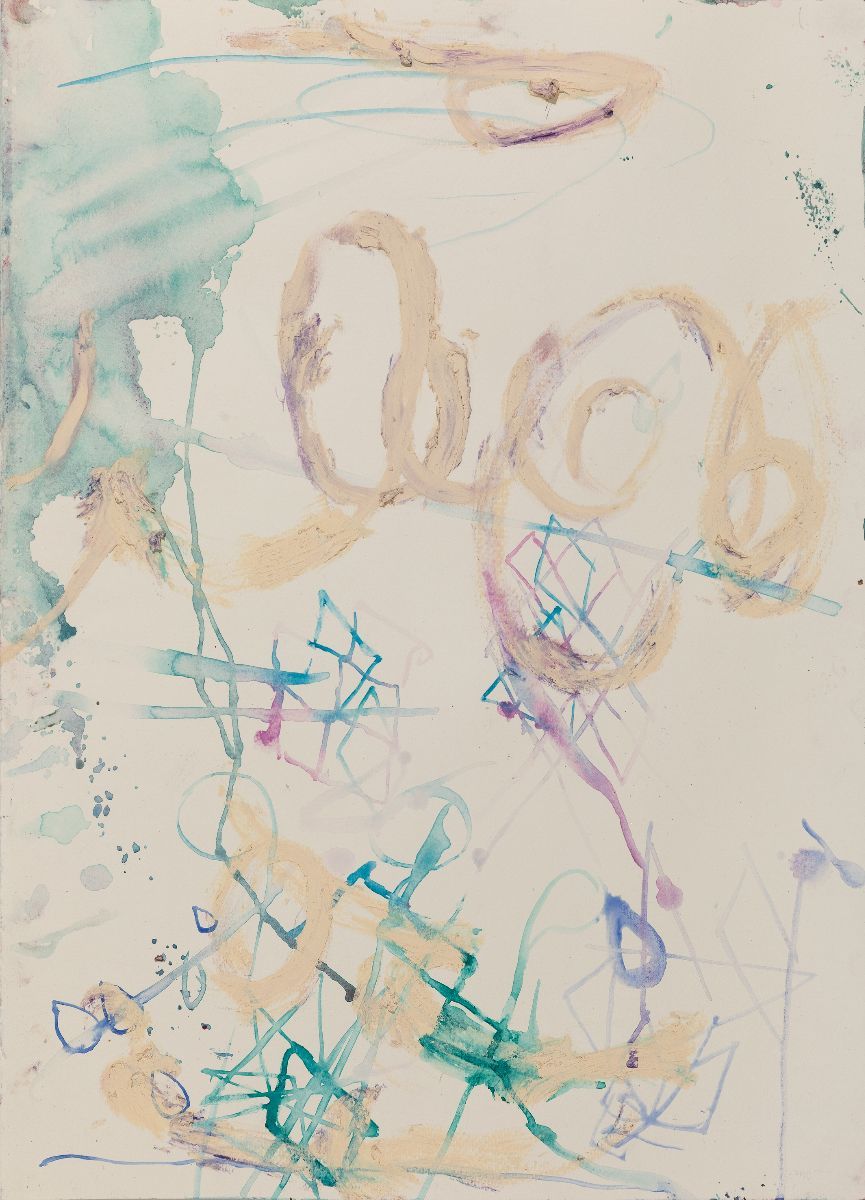

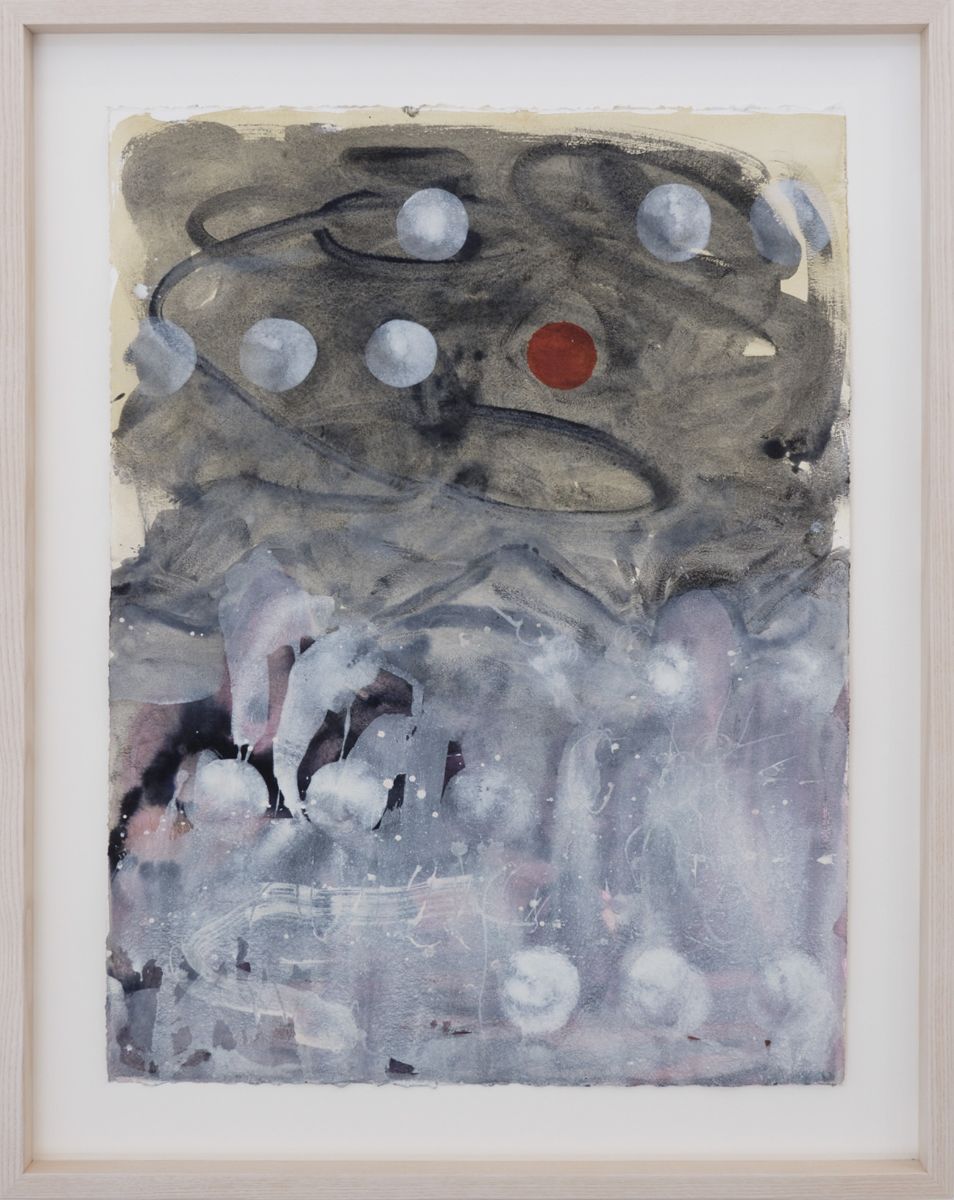

Colour changes in relation to molecules in the atmosphere and the scattering of light; scenes as they curve over the horizon are in lower contrast[1]. While landscape is an important form within Rebekka Steiger’s recent works, her constituent elements do not adhere to the globe; they hover or float, untethered. The horizon is as crisp as the foreground. The white surface of an untitled work from 2019 (as are all works referred to here) is dotted with a granular texture of pink lozenges, the landscape then painted on top in further white, looping outlines. A snow-capped mountain and a tree are more or less the same form, one an inversion of the other. Elongated, they become perhaps liquid, perhaps wind-blown flora. At first boxing the compass seems anchored, featuring a meandering seam of turquoise flowing down from distant mountains towards us, broadening as it comes closer. Yet the crisply outlined shrubs or trees that dot the roadside don’t adhere to the perspectival narrative, happenstance dictates whether they are towering or diminutive. There are ideas of distance and of proximity, weight and lightness in play, but they are paradoxical.

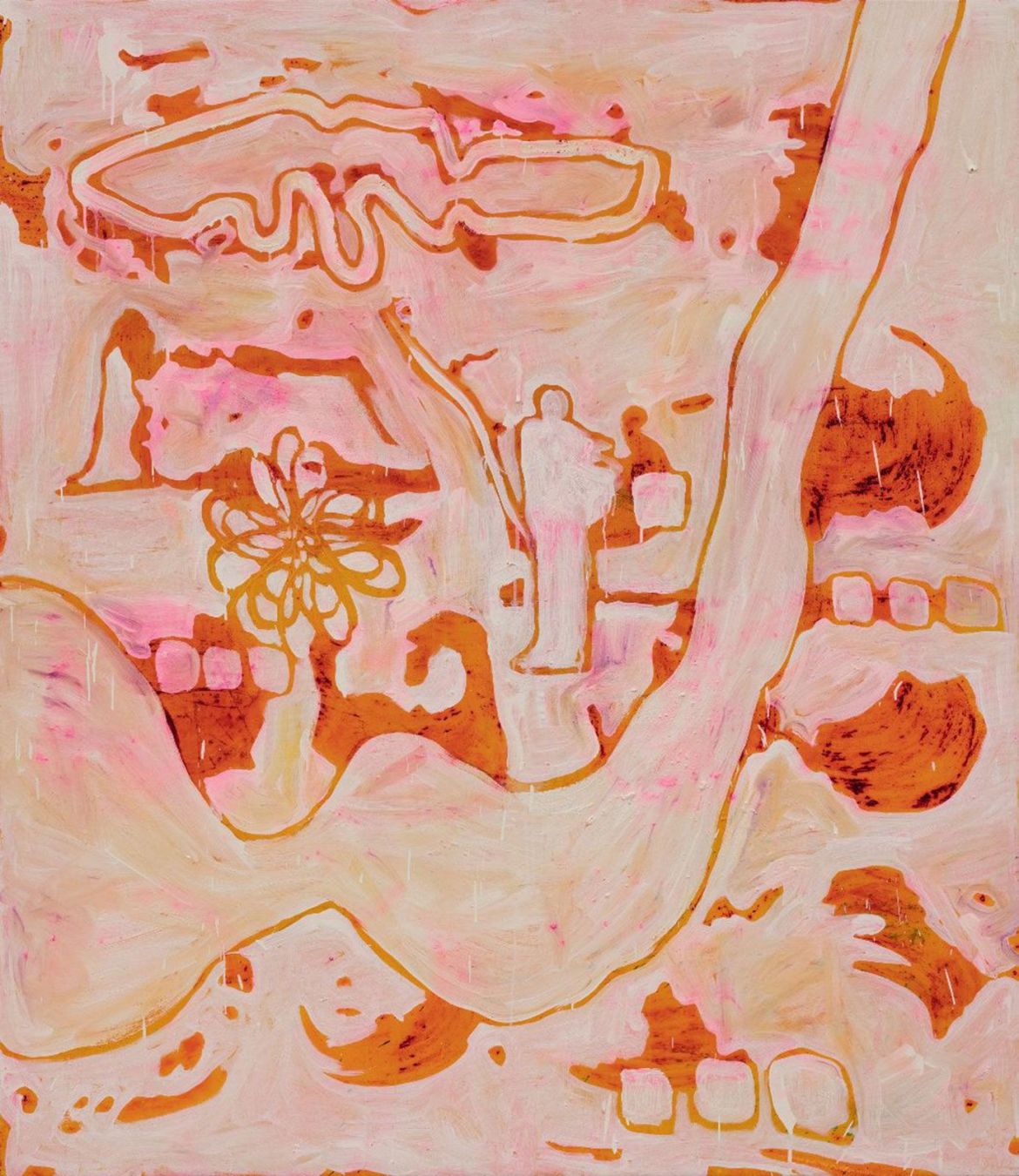

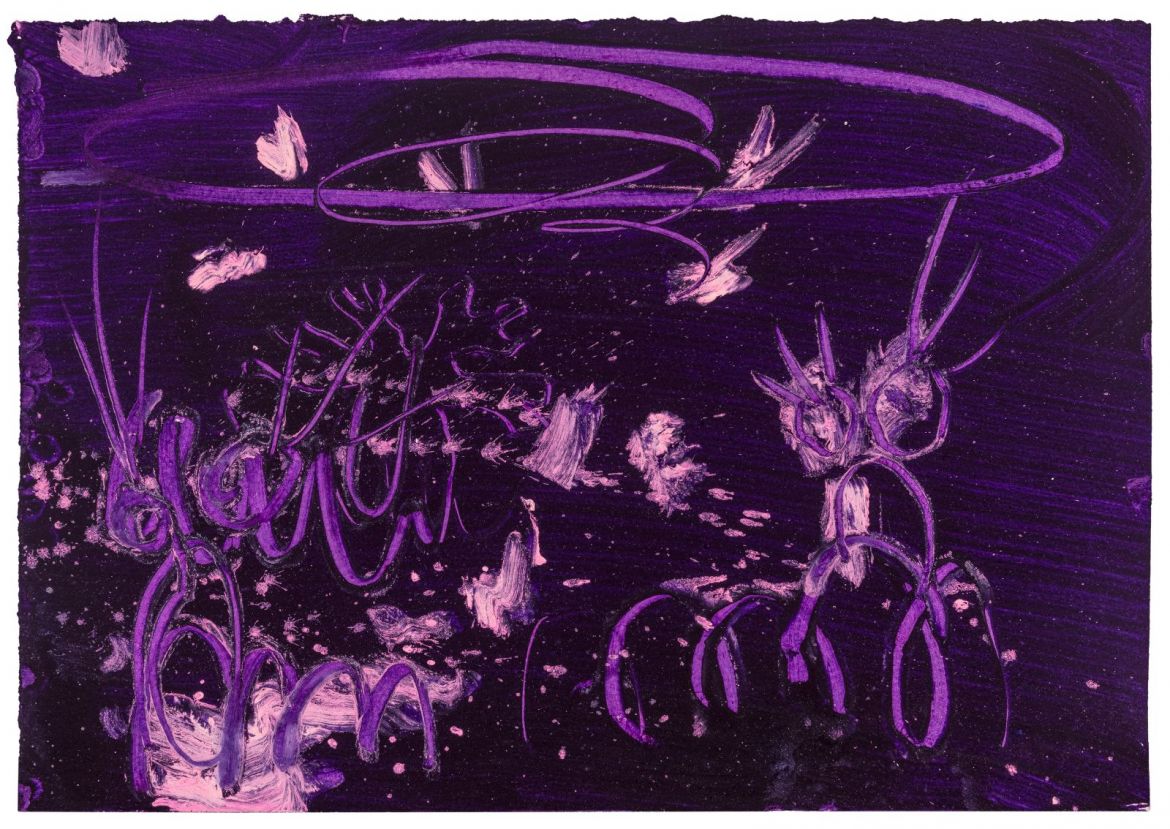

Non-native species: soapbubbles and cacti is blanketed in a localised downpour, while Mauvaise Herbe glows as if under searing sun. Both are landscapes populated and dominated by an eclectic array of flora, with a distant settlement outlined in the latter. Baobab trees in a shorthand outline dot the canvases, their dimensions out of synch: in mauvaise herbe they tower over hills, as they do in soapbubbles, while sprouting up in the foreground too. mauvaise herbe – weeds – triggers a distant memory, of Antoine de Sainte-Exupéry’s Little Prince uprooting the baobab trees that, left to their own devices, would smother his diminutive planet.[2] The works share another plant form, a dot on a stalk: closer to balloons in soapbubbles, maybe a soaring LA palm tree in the other. Or are we under water? Are those balloons buoys straining upwards, are the outlines not trees but coral, bleached because colourful marine algae cannot survive as sea temperatures rise? Though one exudes searing heat and the other liquid movement, in both volatility reigns. Don’t look for a natural habitat; these are composite environments. Environments marked by contemporary realities of migration, transformation and extinction.

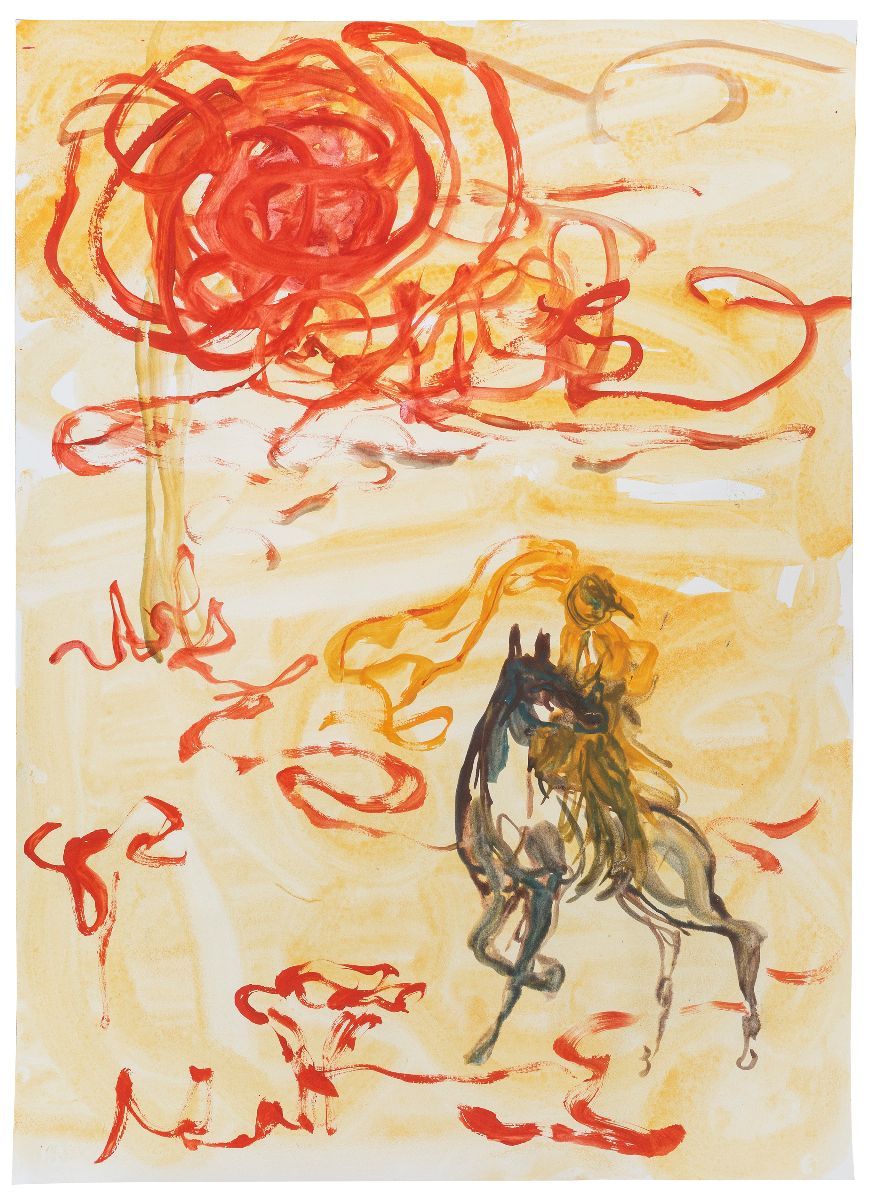

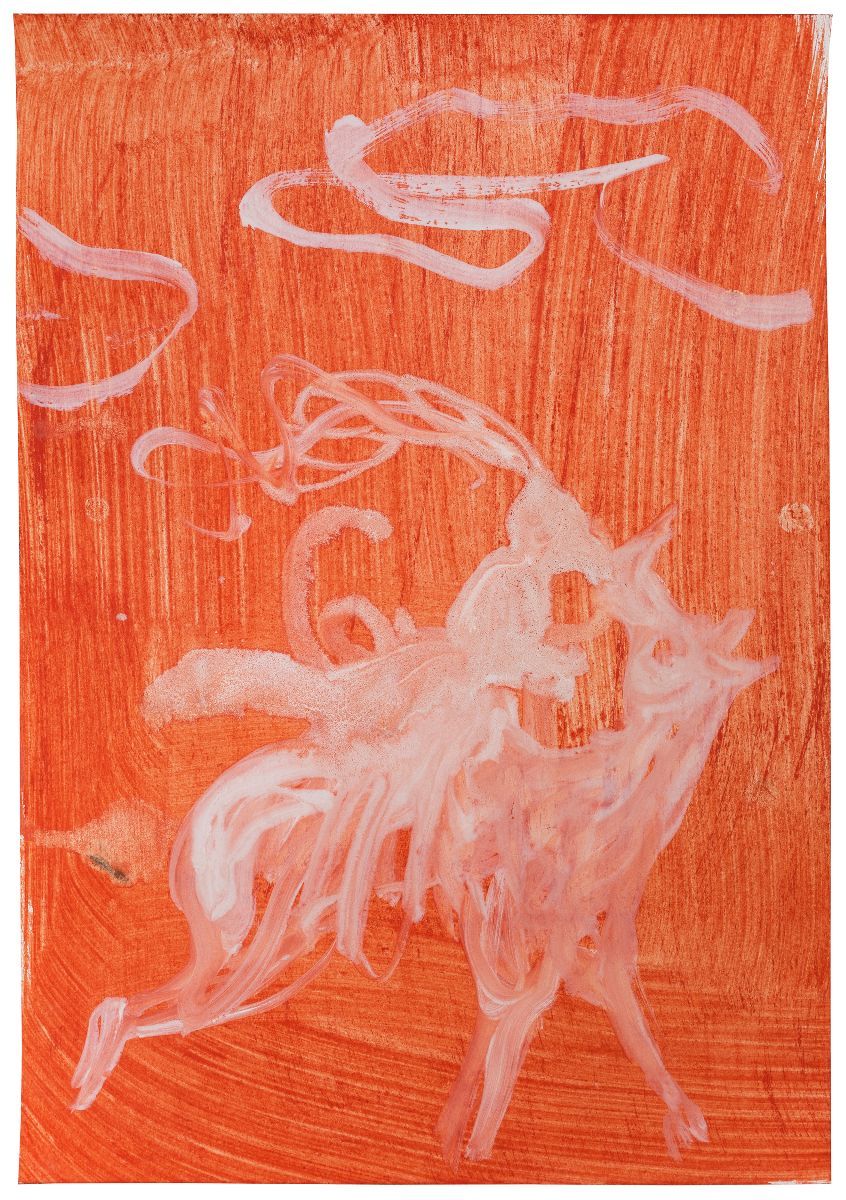

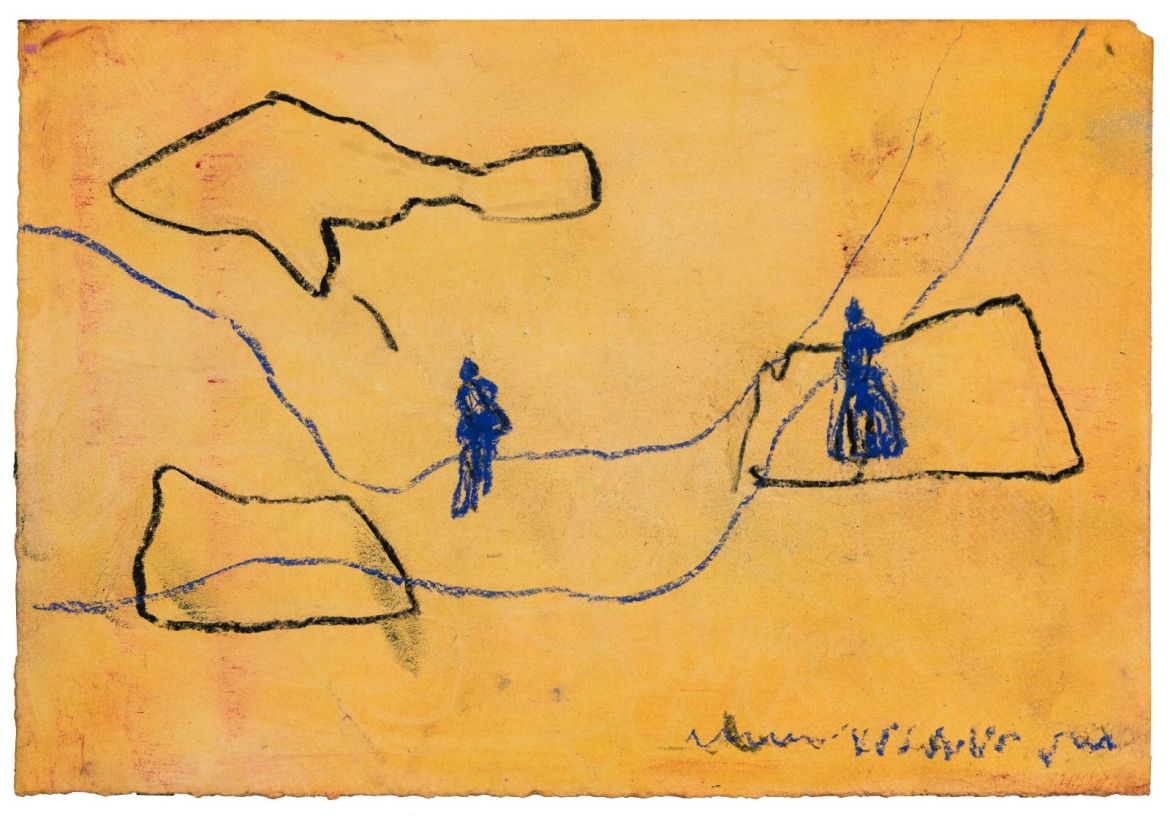

The cast of figures develops gradually. A Mongolian horseman and rider at full tilt, a full-skirted woman and bird-headed figures have been in Steiger’s ensemble for several years; now there are a barfly and scorpions too. I’m reminded of Jack B. Yeats’ latter, breathtakingly expressive works, such as Leaving the Far Point from 1946, in which writhing brushstrokes entangle his figures in their landscapes. Steiger and Yeats’ figures share an upright poise, so they maintain a degree of autonomy even as they merge with their surroundings. In The Sea and the Lighthouse, 1947, the grieving Yeats observes the coast at night, the sky an electric blue that prefigures International Klein Blue by a decade. Yeats’ landscapes are specific, off Sligo on Ireland’s Atlantic west coast in these two examples, yet in his latter works the setting is just as much a psychological as a physical landscape.

Gravity, take two. Steiger’s figures and features are grounded, but may not share the same grounding. Is it that each such feature, geological or animate, is subject to its own gravity? As if all we see of the Little Prince’s planet is the silhouette of a volcano. Akin to Goya etchings, the elements emerge from flatness, or nothingness. The fact of their appearance catalyses a narrative. More psychological, metaphorical landscape.

Yet true to life. My neighbour’s garden spills over into ours. Among the foliage is what I believe is Callicarpa, sometimes called beautyberry, or Schönfrucht in German. Beauty is in the eye of the beholder – though it occurs naturally, it is native to Asia, I find the glaring purple an aberration within a botanical palette. For me it belongs instead in the register of science, in the laboratory, say, where contrast is a tool for identification and, with luck, diagnosis. Steiger’s dead wake is a similar purple. The mountain and sun she outlines notwithstanding, the colour is close to that of the disclosing tablets we chewed on as children to reveal (we gorily hoped) plaque on our teeth. Emphasised further by the fact that Steiger’s image is in negative, brushstrokes and paint splatters glowing white as if they were an immunofluorescent reaction in purple darkness. In accord once more with Yeats, Steiger’s colour could be natural but seems artificial.

The whale. A whale is how the artist describes the large form travelling from the top of the canvas to the left-hand side, with bladder-like bulges in works such as bar pilot. It too seems discrete from the surrounding elements, typically so for Steiger’s ingredients, yet nonetheless surprisingly. If it is a whale it must be deep under water, its movements in the depths unfathomable. Of that most famous of fictional whales, Herman Melville writes ‘One of the wild suggestings referred to […] was the unearthly conceit that Moby-Dick was ubiquitous; that he had actually been encountered in opposite latitudes at one and the same instant of time’[3]. The behemoths we know best today are omnipresent and intangible: governments, they in turn overshadowed by the might of global corporations, networks utterly ensnaring us and data we generate in inexpressibly large quantities.

Instead of a whale I see a tuber. A rhizome, to borrow Deleuze and Guattari’s terminology in 1980’s A Thousand Plateaus. To read the shape this way means ignoring the scale of all other figures around – imagine these are roots in close-up, the kind of roots that are inspiring in their underground, unseen vitality, their unfettered drive to extend and colonise new soil. I don’t know if Deleuze and Guattari, philosopher and psychoanalyst respectively, are concerned with this immodest hunger to extend; their interest lies in decentred structures. And, aptly, they are thoroughly modest, declining at the outset the singular prophet’s role: ‘We are no longer ourselves. […] We have been aided, inspired, multiplied.’[4]

Rebekka Steiger currently lives and works in the city of Beijing. The city’s population is more than 20 million, unfathomable by Swiss standards. What is her landscape? What is landscape to anybody in 2020? The technological revolutions of recent decades have redefined how we see and know the world. It may be that we encounter the pictorial genre most often on a screensaver, where it offers a dream of mediated, not real, reality. Electronic experience infects tangible experience: the differentiation between exterior and interior is blurred, for example, when we always have a portal to another environment in our pocket. Likewise, distance has been overcome – we can be on one continent and speak to another simultaneously. The artist and I did. One might consider that this newfound electronic reach would allow us to move less, but this is not the case. Zygmund Bauman, drawing on Manuel Castells’ work, identifies power in a modern city in its mobility.[5] Power (for which read wealth, industry, influence etc.) flows, in and out of locations, carrying the mobile, well-educated with it, leaving the less flexible in its wake. (Though mobility is often no choice, flight from conflict or climate change being examples.)

How we relate to places has changed too. In another text, Bauman describes the ‘tourist syndrome’.[6] Ad-hoc living, long or short term, encourages us to graze a place, to take what we want and move on. More than ever, superficial interactions through familiar global services, if we pay by Paypal or get a latte at Starbucks, stay in a major hotel chain or log into Netflix, encourage us to stay within our comfort zone when in foreign lands. We become less likely to scratch the surfaces of places we visit, that is, to perceive local differences beyond architecture or customer service. In our own cities, meanwhile, it is equally possible to inhabit the global realm, to live an international life that could be anywhere.

Yet there are other ways of being; resistance to the homogenisation of globalisation is feasible. Escape from the atomisation of the digital too. What if encounters were mutually informative, even enriching? Deleuze and Guattari might indeed help us here. The notion of the tuber is not only applicable to the underground and weighted. They describe a wasp landing on an orchid: ‘Wasp and orchid, as heterogeneous elements, form a rhizome. […] At the same time, something else entirely is going on: not imitation at all but a capture of code, surplus value of code, an increase in valence, a veritable becoming, a becoming-wasp of the orchid and a becoming-orchid of the wasp.’[7]

Artists now address viewers that are rapidly finding themselves untethered from rehearsed ideas of belonging or locality. We are footloose. For good and bad, there is a renegotiation underway of how we relate to our context. Steiger’s figures have art historical ancestry as well as being informed by contemporary forms of imaging, and combining the two they mediate contemporary experience. Her landscapes illustrate how we might perceive a world both real and digital, and thus her landscapes are both actual and metaphorical. In her canvases we can consider how to navigate new notions of native or of belonging. What is the nature of our connection to our landscape and what do we want it to be? How are we inscribing ourselves on or in the world? What is the nature of our encounters? Let us become multiplied, orchid and wasp!

[1] The flattening effect of aerial perspective is heightened in Beijing, where Steiger currently lives and works, where air quality is markedly worse than in Switzerland.

[2] Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, Le Petit Prince, 1943. It is also interesting that Steiger entitles her work Mauvaise Herbe, the French term for weed, with its inherent value judgement, as opposed to the neutral English weed or the German Unkraut, the latter word seeming increasingly absurd as both rewilding and the cultivation of wild flowers flourish.

[3] Herman Melville: The Dover Reader, Dover Publications, Mineola, New York, 2016, p. 291.

[4] A Thousand Plateaus Capitalism and Schizophrenia, Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, translation and foreword by Brian Massumi, The University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, 1987, p. 3.

[5] City of Fears, City of Hopes, Zygmunt Bauman, Goldsmiths College, London, 2003, p. 15.

[6] The Tourist Syndrome: An Interview with Zygmunt Bauman, Adrian Franklin, Tourist Studies, Volume: 3 issue: 2, pp. 205-217, 2003.

[7] Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, ibid., p. 10.

Video: Laura Hadorn

ARTIST INFORMATION

View more information of the artist, please click here.